Blockchain governance: Programming our future

https://medium.com/@FEhrsam/blockchain-governance-programming-our-future-c3bfe30f2d74

Fred Eshram, Nov 2017

This post describes why blockchain governance design is one of the most important problems out there, its critical components, current approaches, potential future approaches, and concludes with suggestions for the community.

Why Blockchain Governance Matters

As with organisms, the most successful blockchains will be those that can best adapt to their environments. Assuming these systems need to evolve to survive, initial design is important, but over a long enough timeline, the mechanisms for change are most important.

As a result, I believe governance is the most vital problem in the space. Other fundamental problems like scalability are arguably best approached by using governance to set the right incentives for people to solve them. Yet little research has gone into governance and it feels poorly understood.

Evolutionary tree of life, from Leonard Eisenberg.

Satoshi showed us the immense power of releasing a blockchain-based incentive structure into the world. A 9 page whitepaper spawned a $150bn cryptocurrency, a computer network bigger than the top 500 supercomputers by 10,000x, and a diverse ecosystem of developers, users, and companies. This was arguably one of the highest leverage actions in human history. It showed the power of blockchains as networks that can connect everyone and bootstrap themselves into existence if well constructed.

We are increasingly living in digital networks, spending an average of 11 hours a day on screens in the US with over half of that on internet connected devices, growing 11% each year. However, these networks are highly centralized (Facebook, Google, Apple, Twitter) and continue to consolidate. In the current model, all of the profit and power of a network is within one company, and you’re either inside or you’re outside. It’s important the networks we live in serve our best interests. With blockchains emerging as the new global infrastructure, we have the opportunity to create vastly different power structures and program the future we want for ourselves.

For these reasons, I believe blockchain governance system design is one of the highest leverage activities known.

A Cambrian Explosion

It’s rare a new government or central bank gets created, and even more rare to see experimentation with a new form of governance when it does.

Blockchains are unique because they 1) allow thousands of governance systems and monetary policies to be tried at the speed of software with 2) in some cases, much lower consequences of failure. As a result, there will be a Cambrian explosion of economic and governance designs where many approaches will be tried in parallel at hyperspeed. To be clear, I am including economic design and monetary policy (said another way, incentive structure) in governance because, like other aspects of the system, they can be modified as time passes.

Many of these attempts will be spectacular failures. With millions of algorithmic central banks we will have millions of crypto George Soroses trying to break the Bank of England. Through this process, blockchains may teach us more about governance in the next 10 years than we have learned from the “real world” in the last 100 years.

Two Critical Components of Governance

1. Incentives

Each group in the system has their own incentives. Those incentives are not always 100% aligned with all other groups in the system. Groups will propose changes over time which are advantageous for them. Organisms are biased towards their own survival. This commonly manifests in changes to the reward structure, monetary policy, or balances of power.

2. Mechanisms for coordination

Since it’s unlikely all groups have 100% incentive alignment at all times, the ability for each group to coordinate around their common incentives is critical for them to affect change. If one group can coordinate better than another it creates power imbalances in their favor.

In practice, a major factor is how much coordination can be done on-chain vs. off-chain, where on-chain coordination makes coordinating easier. In some new blockchains, on-chain coordination allows the rules or even the ledger history itself to be changed.

Current Approaches

What follows is a dissection of the benefits and drawbacks of today’s two largest blockchains: Bitcoin and Ethereum. We are currently in the primordial ooze phase of blockchain governance. Systems are simple and little has been tried.

Bitcoin

Bitcoin was the first successful attempt to create a standalone blockchain. Let’s examine it as a base:

1. Incentives

Developers: increase value of existing token holdings, social recognition, maintain power for control over future direction.

Miners: increase value of existing token holdings, expected future block rewards, and expected future transactions fees.

Users: increase value of existing token holdings, increase functional utility (e.g. store of value, uncensorable transactions, file storage).

2. Mechanisms for coordination

Mostly off-chain. Developers coordinate through the Bitcoin Improvement Proposals (BIPs) process and a mailing list. Miners can coordinate on-chain in the sense that they are creating the chain itself.

Resulting system

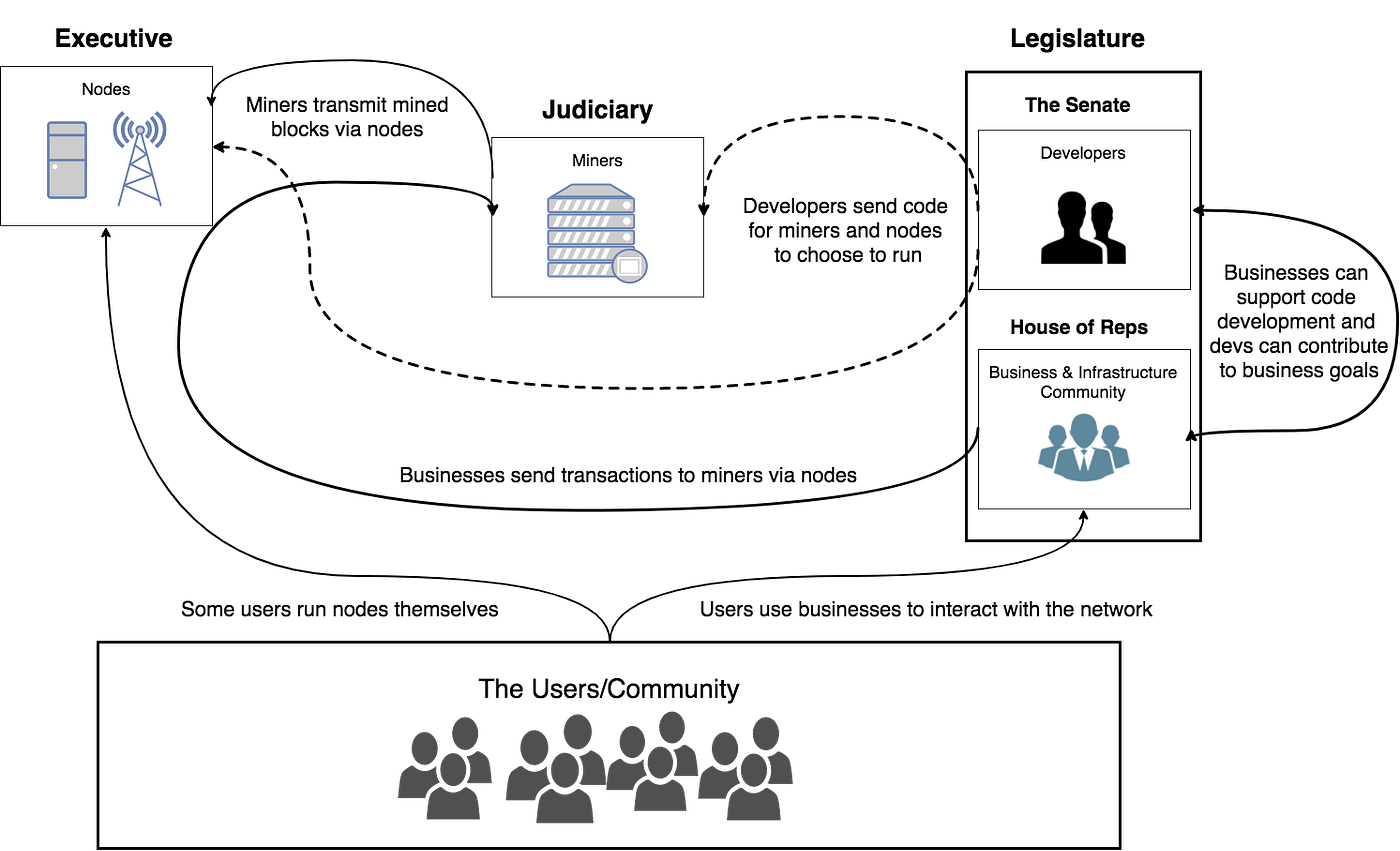

The checks and balances system created is somewhat analogous to the US government and has a number of benefits. Similar to the Senate submitting new bills, developers submit pull requests. Similar to the judiciary, miners decide whether or not to actually adopt the laws in practice. Similar to the executive branch, the nodes of the network can veto by not running a version which aligns with what the miners are running. And similar to citizens, the users can revolt. Finally, economic incentives dictate that it is in everyone’s best interest to maintain trust in the system. For example: if miners alienated all the users, the tokens would decrease in value and they would go out of business. As the first system of its kind, it’s incredible that Bitcoin is still going strong.

Bitcoin as branches of US Government. Image from Buck Perley.

There are risks to the system caused by asymmetries in incentives. Miners push for changes which increase future cumulative transaction fees, while developers don’t care as long as the value of Bitcoin keeps going up. Developers’ direct economic incentives are weak. New developers have little incentive to work on Bitcoin because there is no direct way to earn money by doing it. As a result, they often work on new projects — either by creating Ethereum tokens, entirely new chains, or companies. No new blood entering increases the perception and reality of early developers as the most knowledgable and experienced. This results in a self-reinforcing cycle of more power becoming concentrated in a small group of early core developers, slower technological advancement, and conservatism. Developers are at risk of being bribed since they have a lot of power but weak economic incentives. Some early holders and universities have sponsored developers, but with limited impact thus far.

Similarly, asymmetries in ability to coordinate give miners disproportionate power. Communication amongst miners is easier because they are a small and concentrated group. Since mining is a business with economies of scale, we’d expect a continued trend towards natural monopoly in mining and even greater coordination advantage. As a reference point, 95% of mining power was able to sit on one small stage 2 years ago. Miners can also gain disproportionate power by bribing developers or hiring their own. Finally, the checks and balances system of Bitcoin relies on some level of transparency: for example, users becoming aware of a single miner gaining more than 51% of the hashing power or developers having some level of independence. And a miner who was able to gain >51% of hashing power would be incented to remain anonymous. Rather than sparking a specific catastrophic event, this would cause an unknowing descent into a centralized world of control through censorship and asset freezing.

Ethereum

The systemic incentives and mechanisms of coordination in Ethereum are similar to Bitcoin at the moment.

Dynamics will change as Ethereum moves to proof of stake. The power of miners will be replaced by anyone who holds a sufficient amount of Ether to run a virtual miner (a “validator”). This is especially true as solutions like 1protocol will allow even the smallest Ether holder to participate, flattening the distinction between a miner and a user, and potentially reducing the biggest centralization risk in Bitcoin.

The incentives of core developers remain the same. Coordination around challenging issues has been swifter and smoother than in Bitcoin to date. This is due to 1) a culture more open to change because Ethereum was created as a reaction to what could not be done in a rigid Bitcoin environment and 2) direction from Vitalik who is widely trusted in the community.

Current weaknesses in the model include 1) over reliance on its creator (Vitalik) and 2) like Bitcoin, limited ways to incentivize core development, forcing more projects to create tokens to support themselves. Vitalik is making a conscious effort to step back, which will be a delicate process.

New Chains Experimenting with On-Chain Governance

New blockchains are making it much easier to coordinate by enabling on-chain governance.

Tezos

In Tezos, anyone can submit a change to the governance structure in the form of a code update. An on-chain vote occurs, and if passed, the update makes its way on to a test network. After a period of time on the test network, a confirmation vote occurs, at which point the change goes live on the main network. They call this concept a “self-amending ledger”.

Such a system is interesting because it shifts power towards users and away from the more centralized group of developers and miners. On the developer side, anyone can submit a change, and most importantly, everyone has an economic incentive to do it. Contributions are rewarded by the community with newly minted tokens through inflation funding. This shifts from the current Bitcoin and Ethereum dynamics where a new developer has little incentive to evolve the protocol, thus power tends to concentrate amongst the existing developers, to one where everyone has equal earning power.

This also enables users to directly coordinate on-chain, dramatically increasing their power and reducing the power of miners compared to a system like Bitcoin or Ethereum.

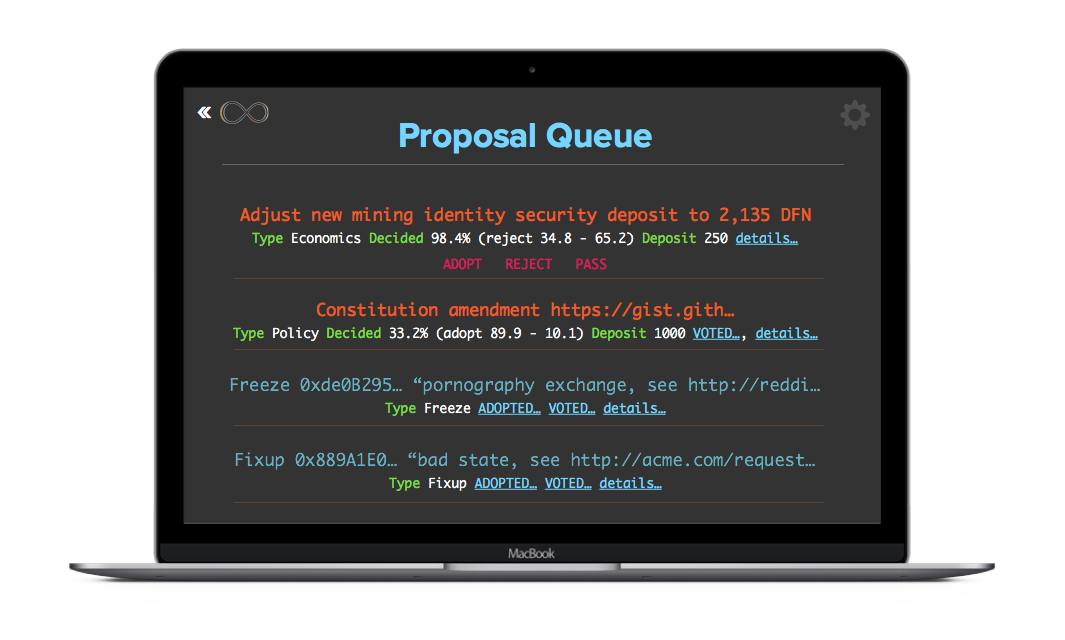

DFINITY

One step further would be a system which allows on-chain votes to the rules of the system like Tezos and direct, retroactive changes to the ledger itself. In other words, if something happens that tokenholders do not like (ex: a hack, a marketplace selling drugs), they can roll back or edit the ledger in addition to the rules of governance themselves. DFINITY, an in-development blockchain, is taking this approach. Proponents of this system point to events like hard fork caused by The DAO hack and the recent $150m Parity multi-sig bug and suggest such events would be much smoother if everyone could just vote to undo them. On the flip side, this system allows direct censorship and peoples’ tokens to be forcibly taken. As we saw with Ethereum’s hard fork to revert The DAO hack, this is possible with existing blockchains, but requires higher friction through off-chain coordination and hard forking instead of on-chain coordination with no forking.

DFINITY is maximally flexible. Depending on what parts of the protocol Tezos allows to be changed, it is possible protocol changes effectively let you re-write the ledger as in DFINITY. As a result, it’s likely these systems will have different voting thresholds for different changes, perhaps requiring a supermajority for some things and a simple majority for others.

The Double-Edged Sword of On-Chain Governance

On-chain governance is a double edged sword. On the upside it helps make sure a process is consistently followed which can increase coordination and fairness. It also allows for quicker decision making. On the downside it’s risky because the metasystem becomes harder to change once instituted. Like anything put directly into code, it can be exploited or gamed more quickly and easily if flawed. Vlad Zamfir, a principal architect of Ethereum’s proof of stake, feels “the risks far outweigh the rewards” and “represent an extremely risky proposition”.

For some use cases, tending towards being static may be good. This may be especially true for store of value. Perhaps lower level protocols should lean toward stasis and conservatism — “measure twice and cut once” — while higher level protocols should be more flexible — “move fast and break things”. In the words of Calvin Coolidge: “it is much more important to kill bad bills than to pass good ones”. Like established companies, some of the more established protocols may be able to watch what new protocols do and adopt techniques which seem to be working. This seems especially true of Ethereum which has shown a willingness to hard fork and the ability to maintain network value through them. Consequently, I’d expect to see the most innovation in the next few years from Ethereum tokens and entirely new chains.

It’s probable we haven’t found the best governance systems yet, which means a more general system which allows many different methods to be tried is valuable, if for nothing more than learning. A more complex system can simulate less complex ones, but the reverse is generally hard.

The most interesting learnings will come from exploring the balance of mutability so systems can evolve and immutability for stability.

Future Approaches

Next we’ll talk about future governance strategies with potential which have yet to be tried.

Futarchy

In futarchy, society defines its values and then prediction markets are used to decide what actions will maximize those values. Said another way: “vote on values, bet on beliefs”. It was originally proposed in 2000 by Robin Hanson, an economics professor at George Mason University.

Ralph Merkle has a particularly eye-opening proposal for a blockchain implementation of futarchy in his paper called DAOs, Democracy, and Governance. In his proposal, every citizen is polled once a year and asked the question “how satisfied were you this year on a scale of 0 to 1?”. Averaged together, these give an overall societal welfare score. A prediction market on this welfare score is developed for every year for the next 100 years, where traders can speculate on the welfare score for any year into the future. An overall future welfare score is then created by averaging the scores for the next 100 years, weighting earlier years more than future years. When a new bill is introduced, there is a 1 week period where markets speculate on whether the overall welfare score will go up or down if the bill is passed. If the bill is passed, the traders who bet on the overall welfare going up now own the overall welfare contracts they bet on. They will make money if they are right and lose money if they are wrong.

Example of futarchy for deciding whether or not to fire a CEO where the value to maximize is revenue. Image from ConsenSys.

Example of futarchy for deciding whether or not to fire a CEO where the value to maximize is revenue. Image from ConsenSys.

This system could be incredibly powerful for a few reasons. First, voting becomes extremely simple. People don’t need to vote, they are just asked about one thing once a year: their satisfaction. Second, people do not need to develop extensive knowledge of candidates or bills. This is important because candidates are often persuasive and bills are complex to the point where it is hard for a domain-specific researcher to understand their implications, let alone an elected official or an average citizen. Instead, we rely on the wisdom of the markets. Like trading in stocks, only people who are extremely well informed on a topic will bet on it — otherwise they are likely to lose money to others who are better informed. Finally, it is a system where market incentives are aligned with societal values.

In futarchy the devil is in the implementation details. Hard problems include the governance metaproblem of how to decide on the societal value(s) to maximize in the first place and making sure people aren’t incented to tactically vote an extreme satisfaction score of 0 or 1 to swing policy.

Setting goal functions is both important and tricky, as there are always unforeseen consequences. For example, in the case of capitalism, this can manifest in rising wealth inequality and environmental externalities. In the case of artificial intelligence, this can manifest in wireheading or rapidly maximizing something at the unexpected expense of other things, commonly illustrated through the example of a paperclip maximizer which destroys everything to build as many paperclips as possible. These are serious concerns, as I believe the most powerful AIs will be bootstrapped into existence on the blockchain by using tokenized incentives for everyone to feed them the best data and algorithms. If this is true, blockchain governance is the largest determinant of our future trajectory as a species. More on this in a future post.

Liquid Democracy

Liquid democracy is system where everyone has the ability to vote themselves, to delegate their vote to someone else, and to remove the delegation of their vote at any time. In the U.S. we do not have a liquid democracy because we cannot vote on many bills directly (our representatives do that for us) and once we elect a representative, they are typically in office for 4 years.

This seems like it will be used in proof of stake blockchains given its simplicity.

Quadratic Voting

Quadratic voting is a system of buying votes, where each additional vote costs twice as much as the one before it. In other words, money buys votes, but with strong diminishing returns. Vitalik proposed a variant on this he calls “quadratic coin lock voting” where N coins let you make N * k votes by locking up those coins for a time period of k². This is a nice modification because it aligns incentives over time: more voting power requires living with your decisions for longer. In a tokenized world with little friction of entering or leaving a community, this is especially important.

Voting with People or Money?

A major problem with one person = one vote systems on the blockchain is their susceptibility to sybil attacks. Near zero cost to create infinite accounts means it’s easy to generate infinite votes. This is why the default model in proof of stake and Ethereum-based token governance is one token = one vote.

Blockchain-based identity systems like Civic can help enable one person = one vote systems. However, anonymity is likely to be preserved in most cryptocurrencies. Identity gives each coin its own unique history, which can be subjectively judged to be more or less clean than that of another coin, causing fungibility to break down. One potential approach is a balance between identity and money: a fully verified identity gets 100% of the voting power of their money, a partially verified identity gets 50%, and an entirely anonymous identity gets 25%.

As mentioned in quadratic voting, other mechanisms which weight community members differently independent of real-world identity are likely to evolve. For example, a new token holder may have diminished voting power until they have been a member of the community for a while, similar to not being able to vote until you are a full citizen of a country.

In any case, today’s world would look a lot different if modern governments ran on voting with money, so this change in defaults is not to be taken lightly.

Finally, reputation within a token community will be critical. This is already shown through indirect means, where Vitalik’s suggestions carry a lot of weight in the Ethereum community. In a liquid democracy system reputation manifests in the number of votes delegated to a particular person. Someone with high reputation and no money could have 10 million Ether delegated to them and have tremendous governing power.

Other Tools

Simple off-chain futures markets have already shown themselves as a powerful tool. In the recently proposed and contentious Bitcoin SegWit2x fork, futures markets speculated on the expected value of SegWit2x vs. non-SegWit2x chains. The markets consistently valued a SegWit2x chain at less than 20% of a non-SegWit2x chain for 3 weeks. Supporters of SegWit2x then called off their forking efforts because they felt they had “not built sufficient consensus”. While it’s hard to know exactly what caused them to reach this conclusion, it seems like futures markets were a strong indicator of lack of support.

Futures markets on Bitcoin’s SegWit2x

Other tools are being built for governance and standardization at different layers. ZeppelinOS is a series of basic libraries which are commonly being used as the base of Ethereum token systems, covering things like token sale mechanics, token vesting, and access controls to the treasury of the project. Aragon is trying to create standard implementations of these systems in the same way Delaware C corporations implement corporations in a standard way.

Forking

It’s worth noting that forking is always an option. Applying Albert Hirschman’s classic voice or exit paradigm for affecting change in a system, voice is governance, weak exit is selling your coins, and strong exit is forking.

We’ve seen many examples of forking so far, and this is great! In physical nations forking is nearly impossible. This was also the case in software until blockchains emerged. They make it easy to take all the code and state of a system and try a new path. In the Web 2.0 world, forking is the equivalent of Facebook allowing any competitor to take their entire database and codebase to a competitor. Don’t like how Facebook is operating it’s newsfeed? Create a fork with all the same code, social connections, and photos.

The ability to fork significantly reduces lock-in and increases diversity, allowing many more paths to be tried than we would ever see in modern governments, central banks, or Web 2.0 companies. As in corporate spinoffs, forking is also beneficial when two niche chains can more effectively serve distinct needs than one chain ineffectively serving both sets of needs.

However, it is still valuable to avoid hard forks when possible. A hard fork is a non-backwards compatible change. Downsides of hard forks include:

Reducing network effects. Not everyone is speaking the same language anymore.

Creating work. Anyone who was using the forked protocol probably had their code broken. In a world that is increasingly interconnected through transparent and trustless code execution, these effects compound.

Reducing trust. Now that we’ve had a breaking change, those previously referencing the protocol must now go outside the blockchain and somehow figure out what the “right” new version is to use.

Because of the dramatically reduced friction for exit, the need for effective voice (governance) is more critical than ever. It is trivial to fork a blockchain and copy all of its code and state. So the value isn’t in the chain of data, it’s in the community and social consensus around a chain. Governance is what keeps communities together and, in turn, gives a token value.

Community Suggestions

For users: Spend more time looking at the governance system of your blockchain, less time on the issue of the day. Current events are just a manifestation of the larger system that caused them. So while it’s easy to get riled up by the news, the highest leverage point for change comes from designing or changing the system, not arguing about its current manifestations.

For developers: Try inflation funding. And if you are creating a new token using a simple 1 token = 1 vote system, consider quadratic coin lock voting as a low risk/high return alternative.

For everyone: Watch and learn from the experiments that will be run on the new on-chain governance systems.

Conclusion

Like organisms, the ability of a blockchain to succeed over time is based on its ability to evolve. This evolution will bring about many decisions on direction, and it is the governance around those decisions which most strongly determine the outcome of the system. If programming in the system is important, the metaprogramming of the system itself is most important.

I believe governance should be the primary focus of investors in the space. The fundamentals of cryptoeconomics and overarching governance schemas of these networks are critical to survival, under-appreciated, and poorly understood. Investors can add significant value through the luxury of being able to observe and learn from multiple projects at one time. They should be active in the governance of the tokens they participate in and transparent with a community if they feel the design of the system can be improved.

We are birthing into existence systems which transcend us. In the same way democracy and capitalism as systems determine so much of the emergent behavior around us, blockchains will do the same with even greater reach. These systems are organisms which take on lives of their own and are more concerned with perpetuating themselves than the individuals which comprise them. As technology stretches these systems to their limits, the implications become more pronounced. So we’d be wise to carefully consider the structure of these systems while we can. Like any new powerful technology, blockchains are a tool that can go in many different directions. Used well, we can create a world with greater prosperity and freedom. Used poorly, we can create systems which lead us to places we didn’t intend to go.

Thanks to Vitalik Buterin, Buck Perley, Vlad Zamfir, Luke Duncan, Brian Armstrong, Ralph Merkle, Arthur Brietman, Julia Galef, Dominic Williams, Luis Iván Cuende, Matt Huang, Demian Brenier, Andy Coravos, Chris Burniske, Jim Posen, Balaji Srinivasan, Scott Nolan, Elad Gil, Chris Dixon, Maksim Stepanenko, Albert Wenger, Simon de la Rouviere, Sophia Cui, Lucas Ryan, Jay Graber, and Jeromy Johnson for conversations and ideas which contributed to this post.

Last updated