Understanding distributed consensus

https://www.preethikasireddy.com/post/lets-take-a-crack-at-understanding-distributed-consensus

Preeth Kasireddy, Nov 2018

Distributed systems can be difficult to understand, mainly because the knowledge surrounding them is distributed. But don’t worry, I’m well aware of the irony. While teaching myself distributed computing, I fell flat on my face many times. Now, after many trials and tribulations, I’m finally ready to explain the basics of distributed systems to you.

Blockchains have forced engineers and scientists to re-examine and question firmly entrenched paradigms in distributed computing.

I also want to discuss the profound effect that blockchain technology has had on the field. Blockchains have forced engineers and scientists to re-examine and question firmly entrenched paradigms in distributed computing. Perhaps no other technology has catalyzed progress faster in this area of study than blockchain.

Distributed systems are by no means new. Scientists and engineers have spent decades researching the subject. But what does blockchain have to do with them? Well, all the contributions that blockchain has made wouldn’t have been possible if distributed systems hadn’t existed first.

Essentially, a blockchain is a new type of distributed system. It started with the advent of Bitcoin and has since made a lasting impact in the field of distributed computing. So, if you want to really know how blockchains work, a great grasp of the principles of distributed systems is essential.

Unfortunately, much of the literature on distributed computing is either difficult to comprehend or dispersed across way too many academic papers. To make matters more complex, there are hundreds of architectures, all of which serve different needs. Boiling this down into a simple-to-understand framework is quite difficult.

Because the field is vast, I had to carefully choose what I could cover. I also had to make generalizations to mask some of the complexity. Please note, my goal is not to make you an expert in the field. Instead, I want to give you enough knowledge to jump-start your journey into distributed systems and consensus.

After reading this post, you’ll walk away with a stronger grasp of:

What a distributed system is,

The properties of a distributed system,

What it means to have consensus in a distributed system,

An understanding of foundational consensus algorithms (e.g. DLS and PBFT), and

Why Nakamoto Consensus is a big deal.

I hope you’re ready to learn, because class is now in session.

What Is a Distributed System?

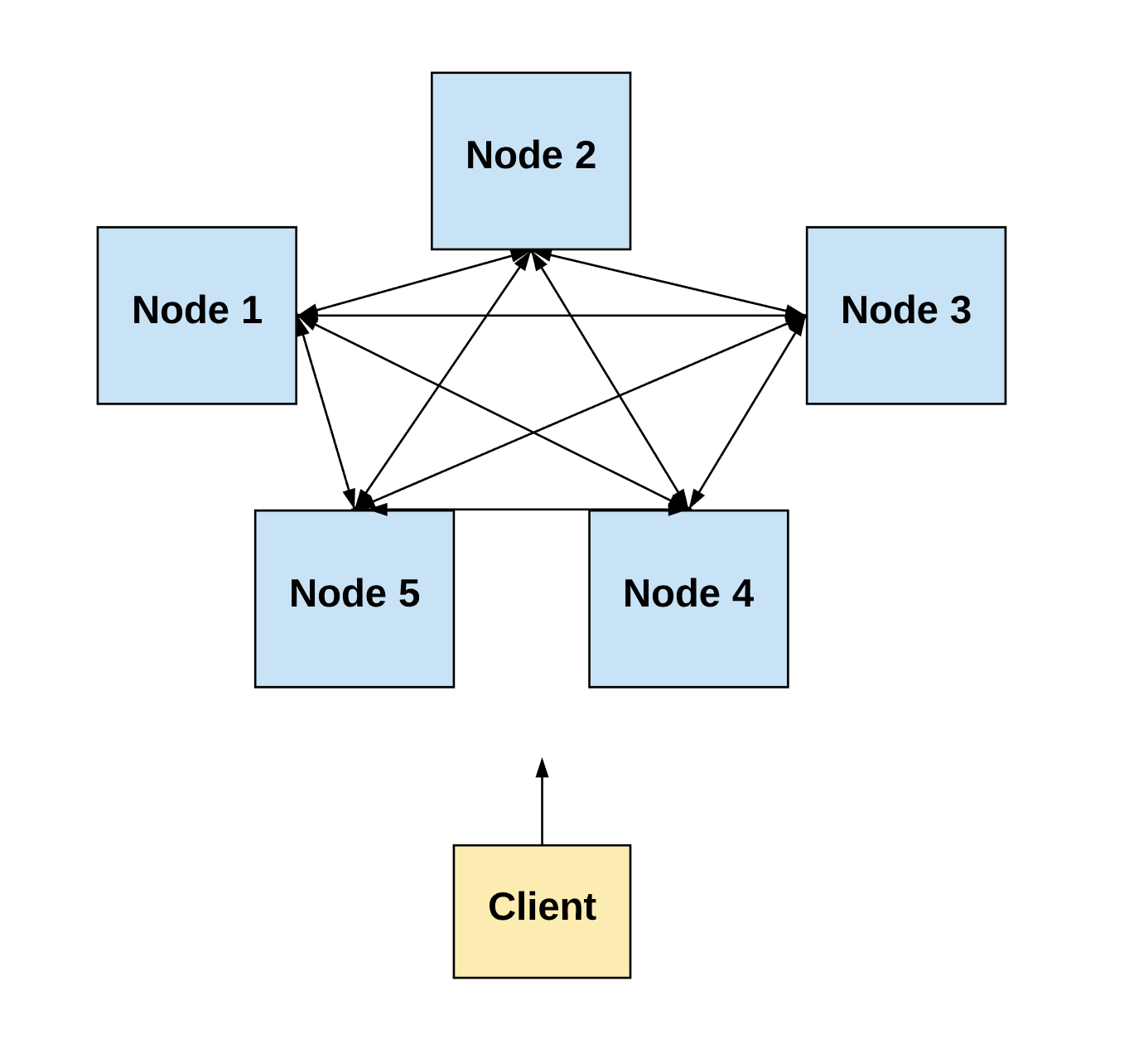

A distributed system involves a set of distinct processes (e.g., computers) passing messages to one another and coordinating to accomplish a common objective (i.e., solving a computational problem).

A distributed system is a group of computers working together to achieve a unified goal.

Simply put, a distributed system is a group of computers working together to achieve a unified goal. And although the processes are separate, the system appears as a single computer to end-user(s).

As I mentioned, there are hundreds of architectures for a distributed system. For example, a single computer can also be viewed as a distributed system: the central control unit, memory units, and input-output channels are separate processes collaborating to complete an objective.

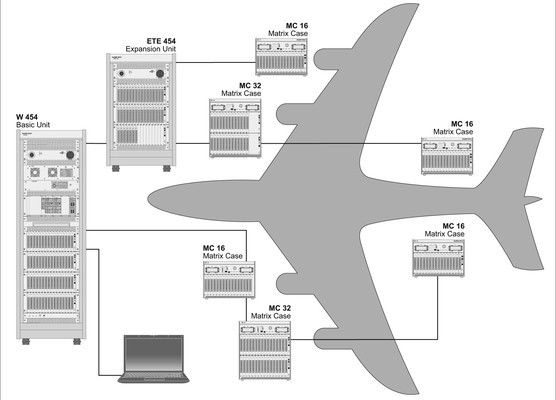

In the case of an airplane, these discrete units work together to get you from Point A to Point B:

In this post, we’ll focus on distributed systems in which processes are spatially-separated computers.

Note: I may use the terms “node,” “peer,” “computer,” or “component” interchangeably with “process.” They all mean the same thing for the purposes of this post. Similarly, I may use the term “network” interchangeably with “system.”

Properties of a Distributed System

Every distributed system has a specific set of characteristics. These include:

A) Concurrency

The processes in the system operate concurrently, meaning multiple events occur simultaneously. In other words, each computer in the network executes events independently at the same time as other computers in the network.

This requires coordination.

Lamport, L (1978). Time, Clocks and Ordering of Events in a Distributed System

B) Lack of a global clock

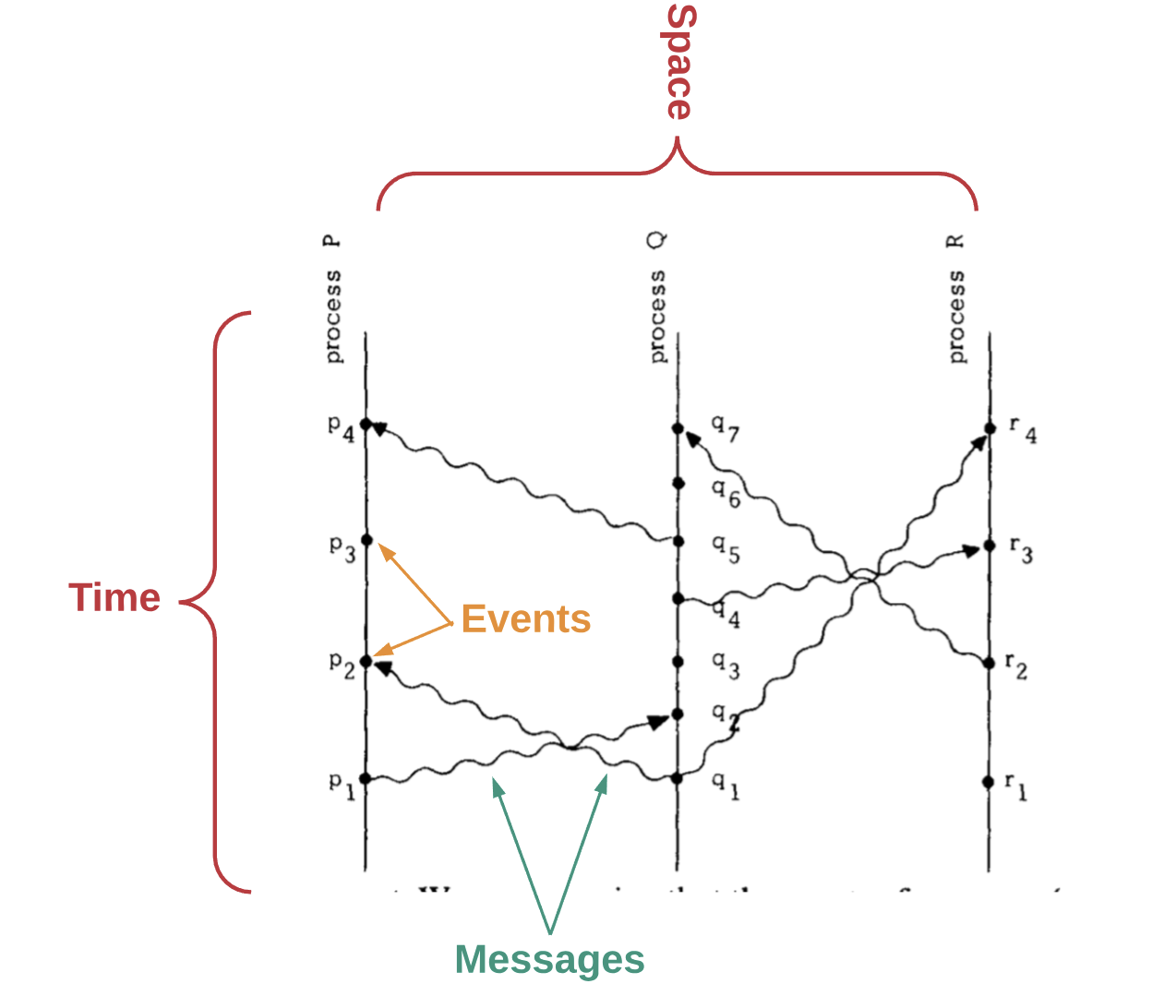

For a distributed system to work, we need a way to determine the order of events. However, in a set of computers operating concurrently, it is sometimes impossible to say that one of two events occurred first, as computers are spatially separated. In other words, there is no single global clock that determines the sequence of events happening across all computers in the network.

In the paper “Time, Clocks and Ordering of Events in a Distributed System,” Leslie Lamport shows how we can deduce whether one event happens before another by remembering the following factors:

Messages are sent before they are received.

Each computer has a sequence of events.

By determining which event happens before another, we can get a partial ordering of events in the system. Lamport’s paper describes an algorithm which requires each computer to hear from every other computer in the system. In this way, events can be totally ordered based on this partial ordering.

However, if we base the order entirely upon events heard by each individual computer, we can run into situations where this order differs from what a user external to the system perceives. Thus, the paper shows that the algorithm can still allow for anomalous behavior.

Finally, Lamport discusses how such anomalies can be prevented by using properly synchronized physical clocks.

But wait — there’s a huge caveat: coordinating otherwise independent clocks is a very complex computer science problem. Even if you initially set a bunch of clocks accurately, the clocks will begin to differ after some amount of time. This is due to “clock drift,” a phenomenon in which clocks count time at slightly different rates.

Essentially, Lamport’s paper demonstrates that time and order of events are fundamental obstacles in a system of distributed computers that are spatially separated.

C) Independent failure of components

A critical aspect of understanding distributed systems is acknowledging that components in a distributed system are faulty. This is why it’s called “fault-tolerant distributed computing.”

It’s impossible to have a system free of faults. Real systems are subject to a number of possible flaws or defects, whether that’s a process crashing; messages being lost, distorted, or duplicated; a network partition delaying or dropping messages; or even a process going completely haywire and sending messages according to some malevolent plan.

It’s impossible to have a system free of faults.

These failures can be broadly classified into three categories:

Crash-fail: The component stops working without warning (e.g., the computer crashes).

Omission: The component sends a message but it is not received by the other nodes (e.g., the message was dropped).

Byzantine: The component behaves arbitrarily. This type of fault is irrelevant in controlled environments (e.g., Google or Amazon data centers) where there is presumably no malicious behavior. Instead, these faults occur in what’s known as an “adversarial context.” Basically, when a decentralized set of independent actors serve as nodes in the network, these actors may choose to act in a “Byzantine” manner. This means they maliciously choose to alter, block, or not send messages at all.

With this in mind, the aim is to design protocols that allow a system with faulty components to still achieve the common goal and provide a useful service.

Given that every system has faults, a core consideration we must make when building a distributed system is whether it can survive even when its parts deviate from normal behavior, whether that’s due to non-malicious behaviors (i.e., crash-fail or omission faults) or malicious behavior (i.e., Byzantine faults).

Broadly speaking, there are two types of models to consider when making a distributed system:

1) Simple fault-tolerance

In a simple fault-tolerant system, we assume that all parts of the system do one of two things: they either follow the protocol exactly or they fail. This type of system should definitely be able to handle nodes going offline or failing. But it doesn’t have to worry about nodes exhibiting arbitrary or malicious behavior.

2A) Byzantine fault-tolerance

A simple fault-tolerant system is not very useful in an uncontrolled environment. In a decentralized system that has nodes controlled by independent actors communicating on the open, permissionless internet, we also need to design for nodes that choose to be malicious or “Byzantine.” Therefore, in a Byzantine fault-tolerant system, we assume nodes can fail or be malicious.

2B) BAR fault-tolerance

Despite the fact that most real systems are designed to withstand Byzantine failures, some experts argue that these designs are too general and don’t take into account “rational” failures, wherein nodes can deviate if it is in their self-interest to do so. In other words, nodes can be both honest and dishonest, depending on incentives. If the incentives are high enough, then even the majority of nodes might act dishonestly.

More formally, this is defined as the BAR model — one that specifies for both Byzantine and rational failures. The BAR model assumes three types of actors:

Byzantine: Byzantine nodes are malicious and trying to screw you.

Altruistic: Honest nodes always follow the protocol.

Rational: Rational nodes only follow the protocol if it suits them.

D) Message passing

As I noted earlier, computers in a distributed system communicate and coordinate by “message passing” between one or more other computers. Messages can be passed using any messaging protocol, whether that’s HTTP, RPC, or a custom protocol built for the specific implementation. There are two types of message-passing environments:

1) Synchronous

In a synchronous system, it is assumed that messages will be delivered within some fixed, known amount of time.

Synchronous message passing is conceptually less complex because users have a guarantee: when they send a message, the receiving component will get it within a certain time frame. This allows users to model their protocol with a fixed upper bound of how long the message will take to reach its destination.

However, this type of environment is not very practical in a real-world distributed system where computers can crash or go offline and messages can be dropped, duplicated, delayed, or received out of order.

2) Asynchronous

In an asynchronous message-passing system, it is assumed that a network may delay messages infinitely, duplicate them, or deliver them out of order. In other words, there is no fixed upper bound on how long a message will take to be received.

What It Means to Have Consensus in a Distributed System

So far, we’ve learned about the following properties of a distributed system:

Concurrency of processes

Lack of a global clock

Faulty processes

Message passing

Next, we’ll focus on understanding what it means to achieve “consensus” in a distributed system. But first, it’s important to reiterate what we alluded to earlier: there are hundreds of hardware and software architectures used for distributed computing.

The most common form is called a replicated state machine.

Replicated State Machine

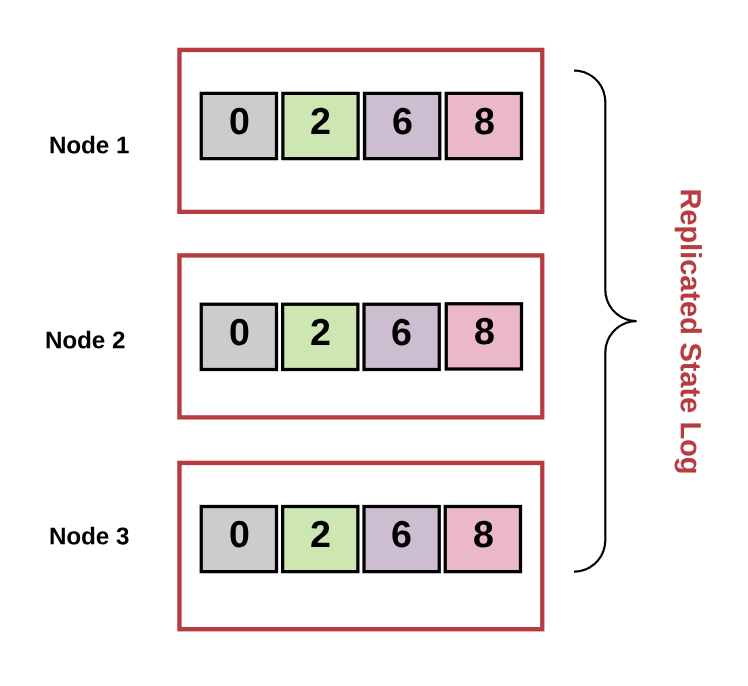

A replicated state machine is a deterministic state machine that is replicated across many computers but functions as a single state machine. Any of these computers may be faulty, but the state machine will still function.

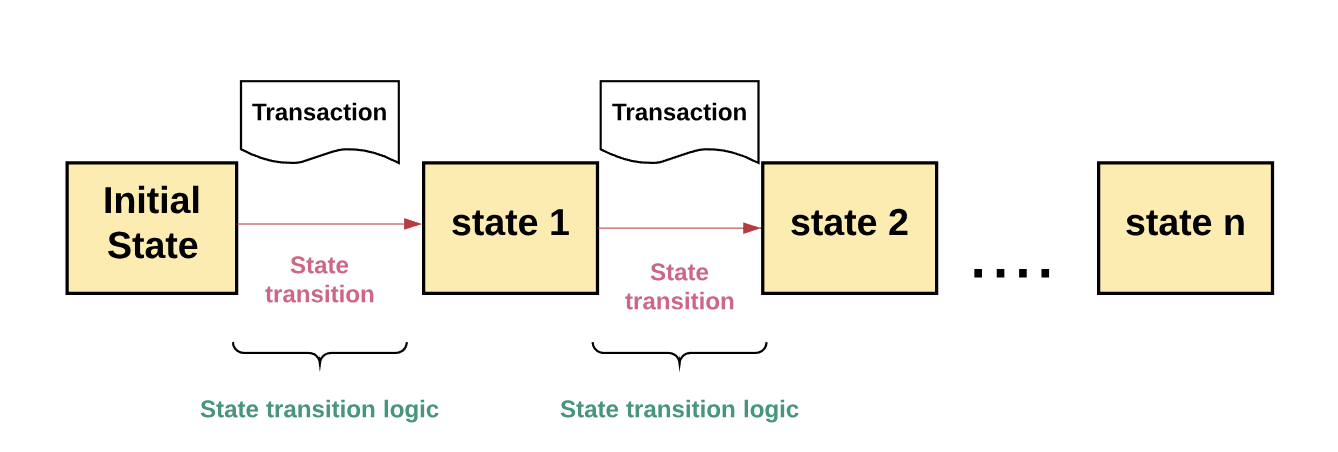

In a replicated state machine, if a transaction is valid, a set of inputs will cause the state of the system to transition to the next state. A transaction is an atomic operation on a database. This means the operations either complete in full or never complete at all. The set of transactions maintained in a replicated state machine is known as a “transaction log.”

The logic for transitioning from one valid state to the next is called the “state transition logic.”

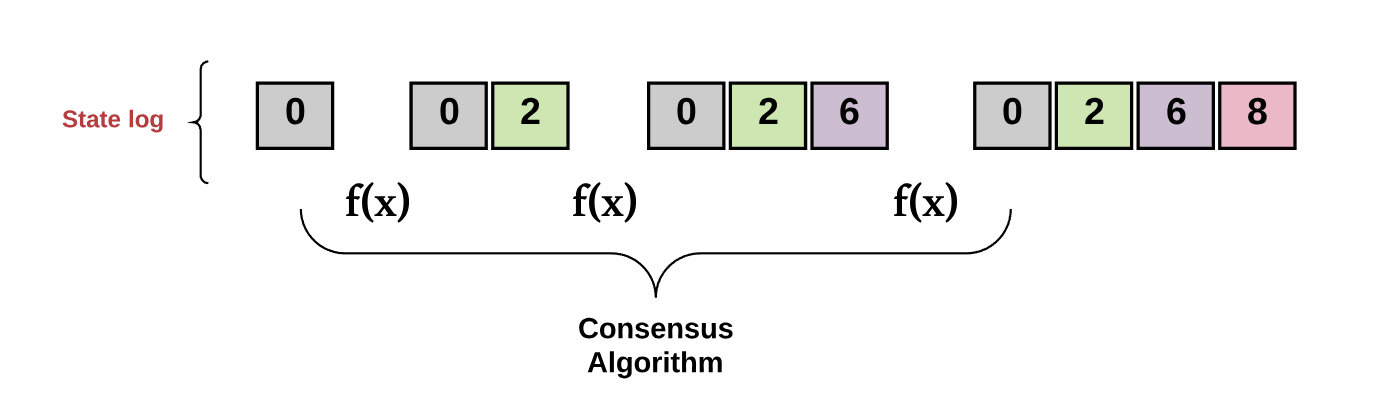

In other words, a replicated state machine is a set of distributed computers that all start with the same initial value. For each state transition, each of the processes decides on the next value. Reaching “consensus” means that all the computers must collectively agree on the output of this value.

In turn, this maintains a consistent transaction log across every computer in the system (i.e., they “achieve a common goal”). The replicated state machine must continually accept new transactions into this log (i.e., “provide a useful service”). It must do so despite the fact that:

Some of the computers are faulty.

The network is not reliable and messages may fail to deliver, be delayed, or be out of order.

There is no global clock to help determine the order of events.

And this, my friends, is the fundamental goal of any consensus algorithm.

The Consensus Problem, Defined

An algorithm achieves consensus if it satisfies the following conditions:

Agreement: All non-faulty nodes decide on the same output value.

Termination: All non-faulty nodes eventually decide on some output value.

Note: Different algorithms have different variations of the conditions above. For example, some divide the Agreement property into Consistency and Totality. Some have a concept of Validity or Integrity or Efficiency. However, such nuances are beyond the scope of this post.

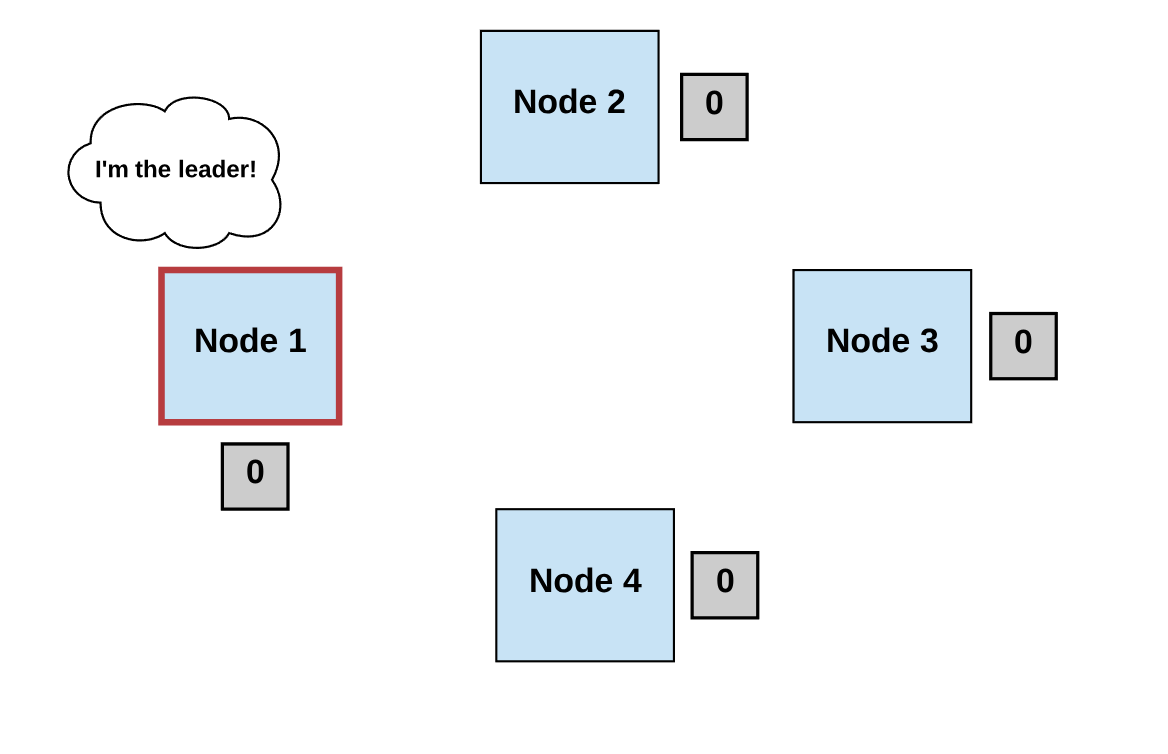

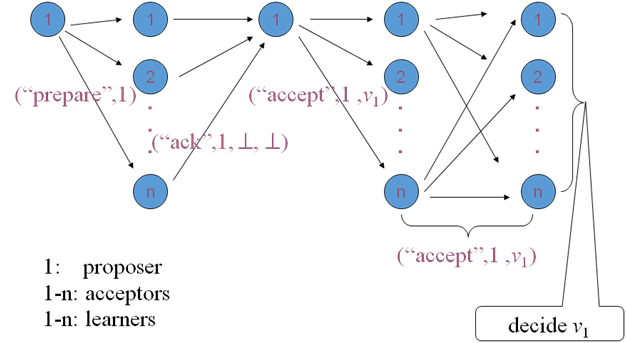

Broadly speaking, consensus algorithms typically assume three types of actors in a system:

Proposers, often called leaders or coordinators.

Acceptors, processes that listen to requests from proposers and respond with values.

Learners, other processes in the system which learn the final values that are decided upon.

Generally, we can define a consensus algorithm by three steps:

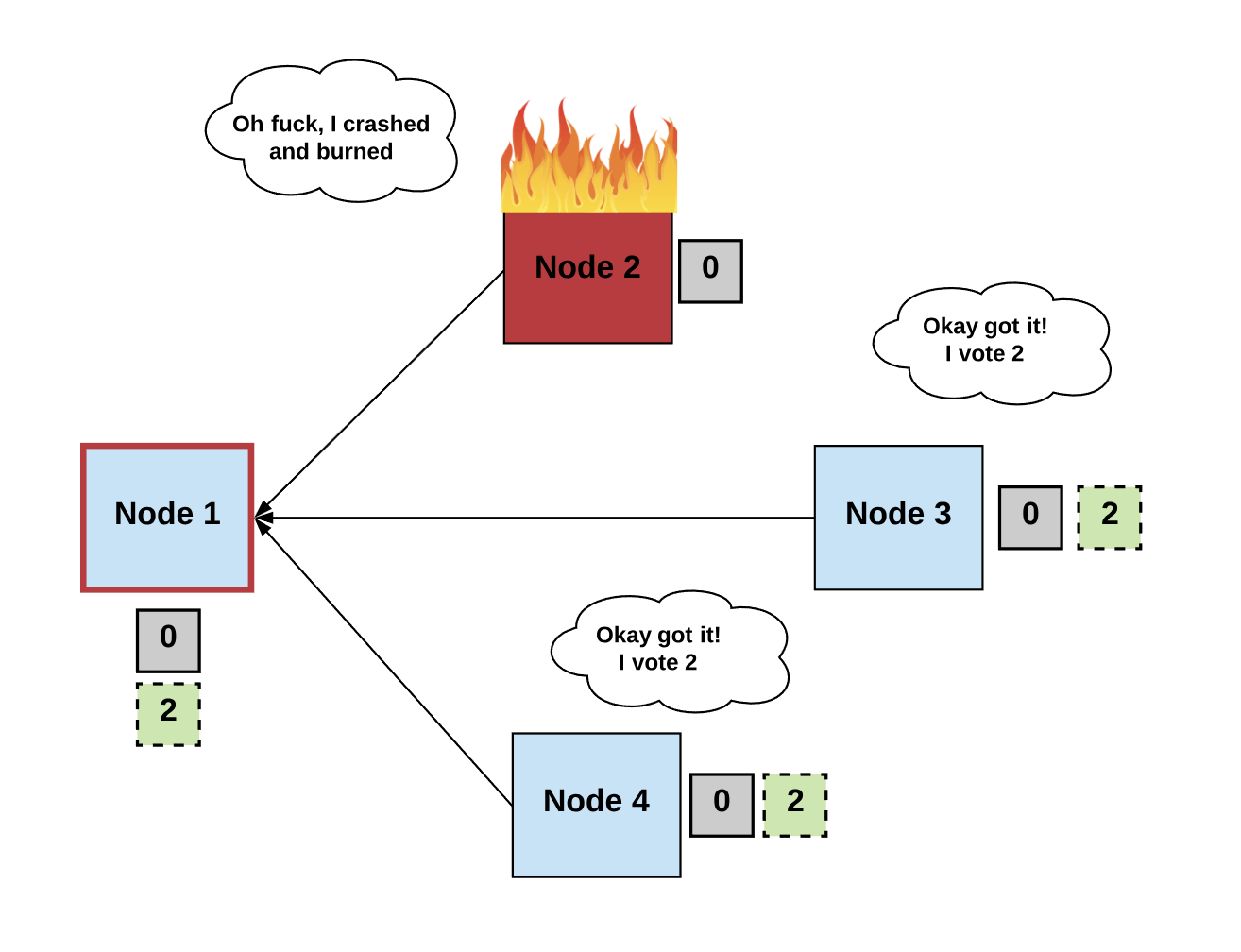

Step 1: Elect

Processes elect a single process (i.e., a leader) to make decisions.

The leader proposes the next valid output value.

Step 2: Vote

The non-faulty processes listen to the value being proposed by the leader, validate it, and propose it as the next valid value.

Step 3: Decide

The non-faulty processes must come to a consensus on a single correct output value. If it receives a threshold number of identical votes which satisfy some criteria, then the processes will decide on that value.

Otherwise, the steps start over.

It’s important to note that every consensus algorithm has different:

Terminology (e.g., rounds, phases),

Procedures for how votes are handled, and

Criteria for how a final value is decided (e.g., validity conditions).

Nonetheless, if we can use this generic process to build an algorithm that guarantees the general conditions defined above, then we have a distributed system which is able to achieve consensus.

Simple enough, right?

FLP impossibility

… Not really. But you probably saw that coming!

Recall how we described the difference between a synchronous system and asynchronous system:

In synchronous environments, messages are delivered within a fixed time frame

In asynchronous environments, there’s no guarantee of a message being delivered.

This distinction is important.

Reaching consensus in a synchronous environment is possible because we can make assumptions about the maximum time it takes for messages to get delivered. Thus, in this type of system, we can allow the different nodes in the system to take turns proposing new transactions, poll for a majority vote, and skip any node if it doesn’t offer a proposal within the maximum time limit.

But, as noted earlier, assuming we are operating in synchronous environments is not practical outside of controlled environments where message latency is predictable, such as data centers which have synchronized atomic clocks.

In reality, most environments don’t allow us to make the synchronous assumption. So we must design for asynchronous environments.

If we cannot assume a maximum message delivery time in an asynchronous environment, then achieving termination is much harder, if not impossible. Remember, one of the conditions that must be met to achieve consensus is “termination,” which means every non-faulty node must decide on some output value.

This is formally known as the “FLP impossibility result.” How did it get this name? Well, I’m glad you asked!

Even a single faulty process makes it impossible to reach consensus among deterministic asynchronous processes.

In their 1985 paper “Impossibility of Distributed Consensus with One Faulty Process,” researchers Fischer, Lynch, and Paterson (aka FLP) show how even a single faulty process makes it impossible to reach consensus among deterministic asynchronous processes. Basically, because processes can fail at unpredictable times, it’s also possible for them to fail at the exact opportune time that prevents consensus from occurring.

This result was a huge bummer for the distributed computing space. Nonetheless, scientists continued to push forward to find ways to circumvent FLP impossibility.

At a high level, there are two ways to circumvent FLP impossibility:

Use synchrony assumptions.

Use non-determinism.

Let’s take a deep dive into each one right now.

Approach 1: Use Synchrony Assumptions

I know what you’re thinking: What the heck does this even mean?

Let’s revisit our impossibility result. Here’s another way to think about it: the FLP impossibility result essentially shows that, if we cannot make progress in a system, then we cannot reach consensus. In other words, if messages are asynchronously delivered, termination cannot be guaranteed. Recall that termination is a required condition that means every non-faulty node must eventually decide on some output value.

But how can we guarantee every non-faulty process will decide on a value if we don’t know when a message will be delivered due to asynchronous networks?

To be clear, the finding does not state that consensus is unreachable. Rather, due to asynchrony, consensus cannot be reached in a fixed time. Saying that consensus is “impossible” simply means that consensus is “not always possible.” It’s a subtle but crucial detail.

One way to circumvent this is to use timeouts. If no progress is being made on deciding the next value, we wait until a timeout, then start the steps all over again. As we’re about to see, this is what consensus algorithms like Paxos and Raft essentially did.

Paxos

Introduced in the 1990s, Paxos was the first real-world, practical, fault-tolerant consensus algorithm. It’s one of the first widely adopted consensus algorithms to be proven correct by Leslie Lamport and has been used by global internet companies like Google and Amazon to build distributed services.

Paxos works like this:

Phase 1: Prepare request

The proposer chooses a new proposal version number (n) and sends a “prepare request” to the acceptors.

If acceptors receive a prepare request (“prepare,” n) with n greater than that of any prepare request they had already responded to, the acceptors send out (“ack,” n, n’, v’) or (“ack,” n, ^ , ^).

Acceptors respond with a promise not to accept any more proposals numbered less than n.

Acceptors suggest the value (v) of the highest-number proposal that they have accepted, if any. Or else, they respond with ^.

Phase 2: Accept request

If the proposer receives responses from a majority of the acceptors, then it can issue an accept request (“accept,” n, v) with number n and value v.

n is the number that appeared in the prepare request.

v is the value of the highest-numbered proposal among the responses.

If the acceptor receives an accept request (“accept,” n, v), it accepts the proposal unless it has already responded to a prepare request with a number greater than n.

Phase 3: Learning phase

Whenever an acceptor accepts a proposal, it responds to all learners (“accept,” n, v).

Learners receive (“accept,” n, v) from a majority of acceptors, decide v, and send (“decide,” v) to all other learners.

Learners receive (“decide,” v) and the decided v.

Phew! Confused yet? I know that was a quite a lot of information to digest.

But wait… There’s more!

As we now know, every distributed system has faults. In this algorithm, if a proposer failed (e.g., because there was an omission fault), then decisions could be delayed. Paxos dealt with this by starting with a new version number in Phase 1, even if previous attempts never ended.

I won’t go into details, but the process to get back to normal operations in such cases was quite complex since processes were expected to step in and drive the resolution process forward.

The main reason Paxos is so hard to understand is that many of its implementation details are left open to the reader’s interpretation: How do we know when a proposer is failing? Do we use synchronous clocks to set a timeout period for deciding when a proposer is failing and we need to move on to the next rank? 🤷

In favor of offering flexibility in implementation, several specifications in key areas are left open-ended. Things like leader election, failure detection, and log management are vaguely or completely undefined.

This design choice ended up becoming one of the biggest downsides of Paxos. It’s not only incredibly difficult to understand but difficult to implement as well. In turn, this made the field of distributed systems incredibly hard to navigate.

By now, you’re probably wondering where the synchrony assumption comes in.

In Paxos, although timeouts are not explicit in the algorithm, when it comes to the actual implementation, electing a new proposer after some timeout period is necessary to achieve termination. Otherwise, we couldn’t guarantee that acceptors would output the next value, and the system could come to a halt.

Raft

In 2013, Ongaro and Ousterhout published a new consensus algorithm for a replicated state machine called Raft, where the core goal was understandability (unlike Paxos).

One important new thing we learned from Raft is the concept of using a shared timeout to deal with termination. In Raft, if you crash and restart, you wait at least one timeout period before trying to get yourself declared a leader, and you are guaranteed to make progress.

But Wait… What about ‘Byzantine’ Environments?

While traditional consensus algorithms (such as Paxos and Raft) are able to thrive in asynchronous environments using some level of synchrony assumptions (i.e. timeouts), they are not Byzantine fault-tolerant. They are only crash fault-tolerant.

Crash-faults are easier to handle because we can model the process as either working or crashed — 0 or 1. The processes can’t act maliciously and lie. Therefore, in a crash fault-tolerant system, a distributed system can be built where a simple majority is enough to reach a consensus.

In an open and decentralized system (such as public blockchains), users have no control over the nodes in the network. Instead, each node makes decisions toward its individual goals, which may conflict with those of other nodes.

In a Byzantine system where nodes have different incentives and can lie, coordinate, or act arbitrarily, you cannot assume a simple majority is enough to reach consensus. Half or more of the supposedly honest nodes can coordinate with each other to lie.

For example, if an elected leader is Byzantine and maintains strong network connections to other nodes, it can compromise the system. Recall how we said we must model our system to either tolerate simple faults or Byzantine faults. Raft and Paxos are simple fault-tolerant but not Byzantine fault-tolerant. They are not designed to tolerate malicious behavior.

The ‘Byzantine General’s Problem’

Trying to build a reliable computer system that can handle processes that provide conflicting information is formally known as the “Byzantine General’s Problem.” A Byzantine fault-tolerant protocol should be able to achieve its common goal even against malicious behavior from nodes.

The paper “Byzantine General’s Problem” by Leslie Lamport, Robert Shostak, and Marshall Pease provided the first proof to solve the Byzantine General’s problem: it showed that a system with x Byzantine nodes must have at least 3x + 1 total nodes in order to reach consensus.

Here’s why:

If x nodes are faulty, then the system needs to operate correctly after coordinating with n minus x nodes (since x nodes might be faulty/Byzantine and not responding). However, we must prepare for the possibility that the x that doesn’t respond may not be faulty; it could be the x that does respond. If we want the number of non-faulty nodes to outnumber the number of faulty nodes, we need at least n minus x minus x > x. Hence, n > 3x + 1 is optimal.

However, the algorithms demonstrated in this paper are only designed to work in a synchronous environment. Bummer! It seems we can only get one or the other (Byzantine or Asynchronous) right. An environment that is both Byzantine and Asynchronous seems much harder to design for.

Why?

In short, building a consensus algorithm that can withstand both an asynchronous environment and a Byzantine one is… well, that would sort of be like making a miracle happen.

Algorithms like Paxos and Raft were well-known and widely used. But there was also a lot of academic work that focused more on solving the consensus problem in a Byzantine + asynchronous setting.

So buckle your seatbelts…

We’re going on a field trip…

To the land of…

Theoretical academic papers!

Okay, okay — I’m sorry for building that up. But you should be excited! Remember that whole “making a miracle” thing we discussed earlier? We’re going to take a look at two algorithms (DLS and PBFT) that brought us closer than ever before to breaking the Byzantine + asynchronous barrier.

The DLS Algorithm

The paper “Consensus in the Presence of Partial Synchrony” by Dwork, Lynch, and Stockmeyer (hence the name “DLS” algorithm) introduced a major advancement in Byzantine fault-tolerant consensus: it defined models for how to achieve consensus in “a partially synchronous system.”

As you may recall, in a synchronous system, there is a known fixed upper bound on the time required for a message to be sent from one processor to another. In an asynchronous system, no fixed upper bounds exist. Partial synchrony lies somewhere between those two extremes.

The paper explained two versions of the partial synchrony assumption:

Assume that fixed bounds exist for how long messages take to get delivered. But they are not known a priori. The goal is to reach consensus regardless of the actual bounds.

Assume the upper bounds for message delivery are known, but they’re only guaranteed to hold starting at some unknown time (also called “Global Standardization Time,” GST). The goal is to design a system that can reach consensus regardless of when this time occurs.

Here’s how the DLS algorithm works:

A series of rounds are divided into “trying” and “lock-release” phases.

Each round has a proposer and begins with each of the processes communicating the value they believe is correct.

The proposer “proposes” a value if at least N − x processes have communicated that value.

When a process receives the proposed value from the proposer, it must lock on the value and then broadcast that information.

If the proposer receives messages from x + 1 processes that they locked on some value, it commits that as the final value.

DLS was a major breakthrough because it created a new category of network assumptions to be made — namely, partial synchrony — and proved consensus was possible with this assumption. The other imperative takeaway from the DLS paper was separating the concerns for reaching consensus in a Byzantine and asynchronous setting into two buckets: safety and liveness.

Safety

This is another term for the “agreement” property we discussed earlier, where all non-faulty processes agree on the same output. If we can guarantee safety, we can guarantee that the system as a whole will stay in sync. We want all nodes to agree on the total order of the transaction log, despite failures and malicious actors. A violation of safety means that we end up with two or more valid transaction logs.

Liveness

This is another term for the “termination” property we discussed earlier, where every non-faulty node eventually decides on some output value. In a blockchain setting, “liveness” means the blockchain keeps growing by adding valid new blocks. Liveness is important because it’s the only way that the network can continue to be useful — otherwise, it will stall.

As we know from the FLP impossibility, consensus can’t be achieved in a completely asynchronous system. The DLS paper argued that making a partial synchrony assumption for achieving the liveness condition is enough to overcome FLP impossibility.

Thus, the paper proved that the algorithms don’t need to use any synchrony assumption to achieve the safety condition.

Pretty straightforward, right? Don’t worry if it’s not. Let’s dig a little deeper.

Remember that if nodes aren’t deciding on some output value, the system just halts. So, if we make some synchrony assumptions (i.e., timeouts) to guarantee termination and one of those fails, it makes sense that this would also bring the system to a stop.

But if we design an algorithm where we assume timeouts (to guarantee correctness), this carries the risk of leading to two valid transaction logs if the synchrony assumption fails.

Designing a distributed system is always about trade-offs.

This would be far more dangerous than the former option. There’s no point in having a useful service (i.e., liveness) if the service is corrupt (i.e., no safety). Basically, having two different blockchains is worse than having the entire blockchain come to a halt.

A distributed system is always about trade-offs. If you want to overcome a limitation (e.g., FLP impossibility), you must make a sacrifice somewhere else. In this case, separating the concerns into safety and liveness is brilliant. It lets us build a system that is safe in an asynchronous setting but still needs some form of timeouts to keep producing new values.

Despite everything that the DLS paper offered, DLS was never widely implemented or used in a real-world Byzantine setting. This is probably due to the fact that one of the core assumptions in the DLS algorithm was to use synchronous processor clocks in order to have a common notion of time. In reality, synchronous clocks are vulnerable to a number of attacks and wouldn’t fare well in a Byzantine fault-tolerant setting.

The PBFT Algorithm

Another Byzantine fault-tolerant algorithm, published in 1999 by Miguel Castro and Barbara Liskov, was called “Practical Byzantine Fault-Tolerance” (PBFT). It was deemed to be a more “practical” algorithm for systems that exhibit Byzantine behavior.

“Practical” in this sense meant it worked in asynchronous environments like the internet and had some optimizations that made it faster than previous consensus algorithms. The paper argued that previous algorithms, while shown to be “theoretically possible,” were either too slow to be used or assumed synchrony for safety.

And as we’ve explained, that can be quite dangerous in an asynchronous setting.

In a nutshell, the PBFT algorithm showed that it could provide safety and liveness assuming (n-1)/3 nodes were faulty. As we previously discussed, that’s the minimum number of nodes we need to tolerate Byzantine faults. Therefore, the resiliency of the algorithm was optimal.

The algorithm provided safety regardless of how many nodes were faulty. In other words, it didn’t assume synchrony for safety. The algorithm did, however, rely on synchrony for liveness. At most, (n-1)/3 nodes could be faulty and the message delay did not grow faster than a certain time limit. Hence, PBFT circumvented FLP impossibility by using a synchrony assumption to guarantee liveness.

The algorithm moved through a succession of “views,” where each view had one “primary” node (i.e., a leader) and the rest were “backups.” Here’s a step-by-step walkthrough of how it worked:

A new transaction happened on a client and was broadcast to the primary.

The primary multicasted it to all the backups.

The backups executed the transaction and sent a reply to the client.

The client wanted x + 1 replies from backups with the same result. This was the final result, and the state transition happened.

If the leader was non-faulty, the protocol worked just fine. However, the process for detecting a bad primary and reelecting a new primary (known as a “view change”) was grossly inefficient. For instance, in order to reach consensus, PBFT required a quadratic number of message exchanges, meaning every computer had to communicate with every other computer in the network.

Note: Explaining the PBFT algorithm in full is a blog post all on its own! We’ll save that for another day ;).

While PBFT was an improvement over previous algorithms, it wasn’t practical enough to scale for real-world use cases (such as public blockchains) where there are large numbers of participants. But hey, at least it was much more specific when it came to things like failure detection and leader election (unlike Paxos).

It’s important to acknowledge PBFT for its contributions. It incorporated important revolutionary ideas that newer consensus protocols (especially in a post-blockchain world) would learn from and use.

For example, Tendermint is a new consensus algorithm that is heavily influenced by PBFT. In their “validation” phase, Tendermint uses two voting steps (like PBFT) to decide on the final value. The key difference with Tendermint’s algorithm is that it’s designed to be more practical.

For instance, Tendermint rotates a new leader every round. If the current round’s leader doesn’t respond within a set period of time, the leader is skipped and the algorithm simply moves to the next round with a new leader. This actually makes a lot more sense than using point-to-point connections every time there needs to be a view-change and a new leader elected.

Approach 2: Non-Determinism

As we’ve learned, most Byzantine fault-tolerant consensus protocols end up using some form of synchrony assumption to overcome FLP impossibility. However, there is another way to overcome FLP impossibility: non-determinism.

Enter: Nakamoto Consensus

As we just learned, in traditional consensus, f(x) is defined such that a proposer and a bunch of acceptors must all coordinate and communicate to decide on the next value.

Traditional consensus doesn’t scale well.

This is too complex because it requires knowing every node in the network and every node communicating with every other node (i.e., quadratic communication overhead). Simply put, it doesn’t scale well and doesn’t work in open, permissionless systems where anyone can join and leave the network at any time.

The brilliance of Nakamoto Consensus is making the above probabilistic. Instead of every node agreeing on a value, f(x) works such that all of the nodes agree on the probability of the value being correct.

Wait, what does that even mean?

Byzantine-fault tolerant

Rather than electing a leader and then coordinating with all nodes, consensus is decided based on which node can solve the computation puzzle the fastest. Each new block in the Bitcoin blockchain is added by the node that solves this puzzle the fastest. The network continues to build on this timestamped chain, and the canonical chain is the one with the most cumulative computation effort expended (i.e., cumulative difficulty).

The longest chain not only serves as proof of the sequence of blocks, but proof that it came from the largest pool of CPU power. Therefore, as long as a majority of CPU power is controlled by honest nodes, they’ll continue to generate the longest chain and outpace attackers.

Block rewards

Nakamoto Consensus works by assuming that nodes will expend computational efforts for the chance of deciding the next block. The brilliance of the algorithm is economically incentivizing nodes to repeatedly perform such computationally expensive puzzles for the chance of randomly winning a large reward (i.e., a block reward).

Sybil resistance

The proof of work required to solve this puzzle makes the protocol inherently Sybil-resistant. No need for PKI or any other fancy authentication schemes.

Peer-to-peer gossip

A major contribution of Nakamoto Consensus is the use of the gossip protocol. It’s more suitable for peer-to-peer settings where communication between non-faulty nodes can’t be assumed. Instead, we assume a node is only connected to a subset of other nodes. Then we use the peer-to-peer protocol where messages are being gossiped between nodes.

Not “technically” safe in asynchronous environments

In Nakamoto consensus, the safety guarantee is probabilistic — we’re growing the longest chain, and each new block lowers the probability of a malicious node trying to build another valid chain.

Therefore, Nakamoto Consensus does not technically guarantee safety in an asynchronous setting. Let’s take a second to understand why.

For a system to achieve the safety condition in an asynchronous setting, we should be able to maintain a consistent transaction log despite asynchronous network conditions. Another way to think about it is that a node can go offline at any time and then later come back online, and use the initial state of the blockchain to determine the latest correct state, regardless of network conditions. Any of the honest nodes can query for arbitrary states in the past, and a malicious node cannot provide fraudulent information that the honest nodes will think is truthful.

Nakamoto Consensus does not technically guarantee safety in an asynchronous setting.

In previous algorithms discussed in this post, this is possible because we are deterministically finalizing a value at every step. As long as we terminate on each value, we can know the past state. However, the reason Bitcoin is not “technically” asynchronously safe is that it is possible for there to be a network partition that lets an attacker with a sufficiently large hash power on one side of the partition to create an alternative chain faster than the honest chain on the other side of the partition — and on this alternative chain, he can try to change one of his own transactions to take back money he spent.

Admittedly, this would require the attacker to gain a lot of hashing power and spend a lot of money.

In essence, the Bitcoin blockchain’s immutability stems from the fact that a majority of miners don’t actually want to adopt an alternative chain. Why? Because it’s too difficult to coordinate enough hash power to get the network to adopt an alternative chain. Put another way, the probability of successfully creating an alternative chain is so low, it’s practically negligible.

Nakamoto vs. Traditional Consensus

For practical purposes, Nakamoto Consensus is Byzantine fault-tolerant. But it clearly doesn’t achieve consensus the way consensus researchers would traditionally assume. Therefore, it was initially seen as being completely out of the Byzantine fault-tolerant world.

By design, the Nakamoto Consensus makes it possible for any number of nodes to have open participation, and no one has to know the full set of participants. The importance of this breakthrough can’t be overstated. Thank you, Nakamoto.

Simpler than previous consensus algorithms, it eliminates the complexity of point-to-point connections, leader election, quadratic communication overhead, etc. You just launch the Bitcoin protocol software on any computer and start mining.

This makes it easily deployable in a real-world setting. It is truly the more “practical” cousin of PBFT.

Conclusion

And there you have it — the brief basics of distributed systems and consensus. It has been a long, winding journey of research, roadblocks, and ingenuity for distributed computing to get this far. I hope this post helps you understand the field at least a tiny it better.

Nakamoto Consensus is truly an innovation that has allowed a whole new wave of researchers, scientists, developers, and engineers to continue breaking new ground in consensus protocol research.

And there’s an entirely new family of protocols being developed that go beyond Nakamoto Consensus. Proof-of-Steak, anyone? ;) But I’ll save that for the next post — stay tuned!

Last updated